Literary Conversations With a French Accent

While reading in our living room lined with bookshelves, I hear a conversation underway that spans centuries. The voices are peppered with observations born of personal trials and revelations experienced over the course of their collective lives. They are a babble of French spoken by a 16th century French essayist, America’s founding foodie, a 19th century French novelist, a Hungarian-born journalist and author, a Russian count with a fondness for French cuisine and wines, and an expat cowgirl chef from Texas who cooks with a French accent in Paris.

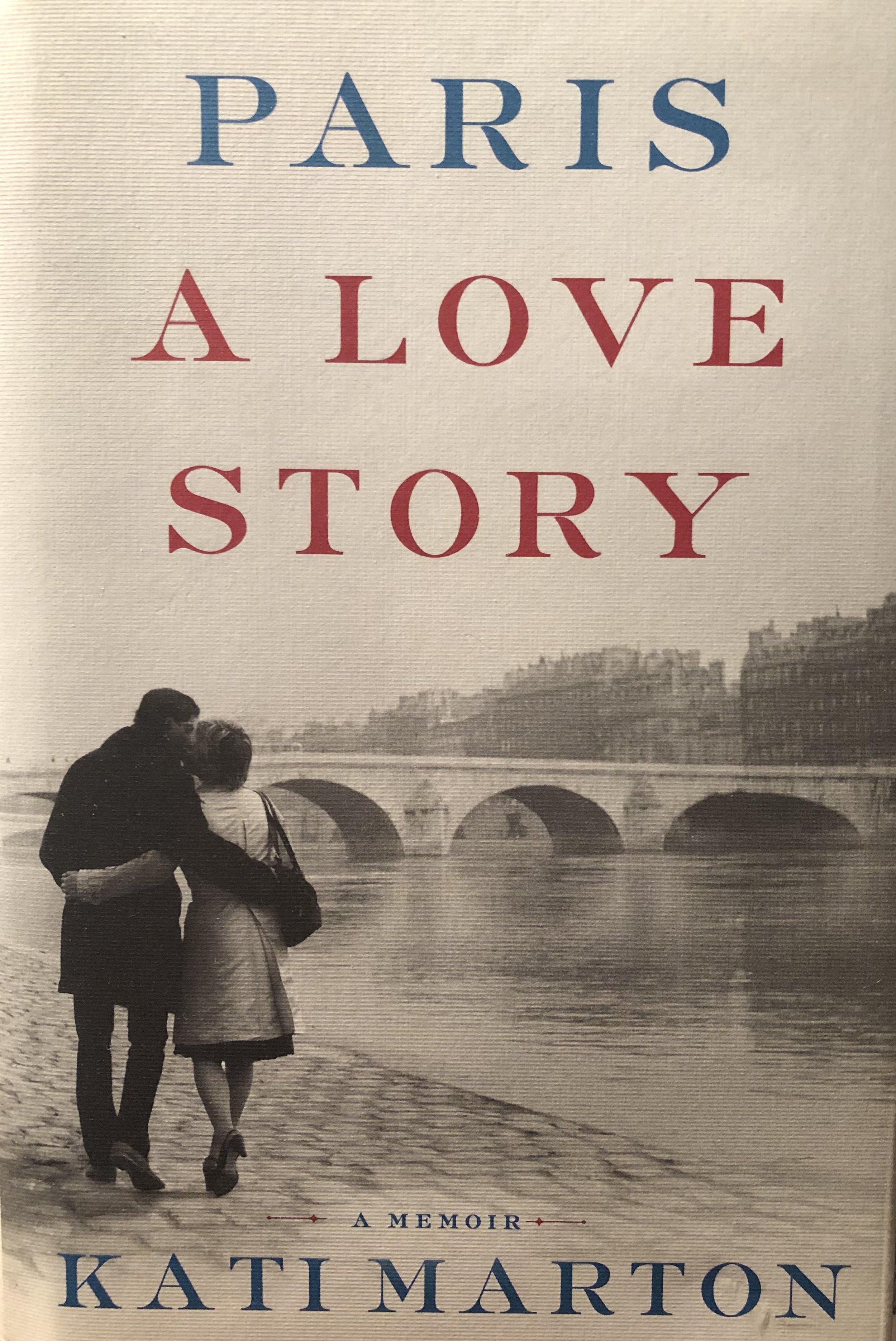

I’m re-reading Kati Marton’s 2012 memoir “Paris: A Love Story.” It chronicles the role that Paris played in her life for decades—first as a student in the late 60s studying at the Sorbonne, then as a journalist when she met and married ABC foreign correspondent Peter Jennings, fifteen years later as an award-winning author and wife of U.S. diplomat Richard Holbrooke following a divorce, and finally after Holbrooke’s sudden death in 2010.

Marton and I are close in age. I follow her voice as she moves through the city's familiar arrondissements, crossing from Left Bank to Right en route to the Place de Voges, to the very cafe where Kit and I ordered frothy cappuccinos and croissants the first morning we experienced Paris together. “I didn’t get to Paris in the 60s,” I tell Kati. “Life took me instead to Southeast Asia where my high school French resurfaced during travels to Cambodia and Laos just before Communism and civil war closed their borders to the world and changed everything.”

“Richard was also there in the late 60s,” Kati remarks. “Perhaps your paths crossed.” Those were the years before computers, email, iPhones and iPads. Kati and I recall writing letters to our parents on flimsy, blue aerograms that were both stationery and envelope wrapped into one. Our mothers saved every letter chronicling our grand dreams and bold adventures.

Back in Paris, Marton recalls attending a class at the Sorbonne's Grand Amphithéâtre lecture hall, where a professor was speaking about Michel de Montaigne—the 16th century humanist credited with inventing the literary form of the essay. "I dove into Montaigne's Essays,” Kati recalls, “and began a lifelong relationship with the man and his words."

Ironically, I tell her I’ve just been reintroduced to Montaigne while reading “A Gentleman in Moscow” aloud to Kit. The book’s author Amor Towles weaves references to Montaigne’s essays throughout the story of Count Alexander Rostov who is sentenced in 1922 to live the rest of his life in the confines of Metropol Hotel in Moscow following the Russian Revolution. Four years after being forced to downsize from his former hotel suite to a tiny room in the belfry, Rostov turns to a weighty volume containing Montaigne’s 107 essays to help pass the time. To survive, the count must adjust to his dilemma.

Towle’s explains— “Having acknowledged that man must master his own circumstances or otherwise be mastered by them, the Count thought it worth considering how one was most likely to achieve this aim when one has been sentenced to a life of confinement.” Thus, the Count sets out to master his radically altered circumstances as a nonperson in Russia’s new regime.

While reading Montaigne’s essays, Rostov comes upon a proverb by Seneca. “The mind anxious about the future is unhappy.” Applying the proverb to his own life, the count is able to balance the tumultuous political climate outside the doors of Moscow’s Metropol Hotel and those going on around him within its walls. Over the next thirty years, his friendships after becoming a waiter in the hotel’s internationally acclaimed restaurant provide him with the most delicious and meaningful chapters in his life.

I sense that Montaigne would be pleased with Towles’ book. Joining in the literary conversation underway, the essayist now reveals his own tale—"In 1580, I left teaching to travel for a year. Seeking truth, I decided to spend the second half of my life settling the ancient question, ‘Who am I?’’’

Upon hearing the very question that plagued Jean Valjean in his classic novel, Les Misérables, Victor Hugo now joins in. “Every French child learns the date February 20, 1571—Montaigne’s 38th birthday, the day when he retreated to the tower of his family castle near Bordeaux and began to write. His 107 ‘essays’ or ‘trials’ were utterly original and radical. He was 'the first modern man.'"

The voice of America’s third President—familiar with the essay form and enamored with everything French—now enters the conversation from the pages of Thomas Jefferson's Crème Brûlée, a book by Thomas J. Craughwell. Jefferson recounts his travels to Paris in 1784 with one of his slaves, 19-year-old James Hemings. "While I studied the cultivation of French crops and grapes for winemaking," noted Jefferson, "James learned the marvels of pasta, French fries, Champagne, macaroni and cheese, and crème brûlée.”

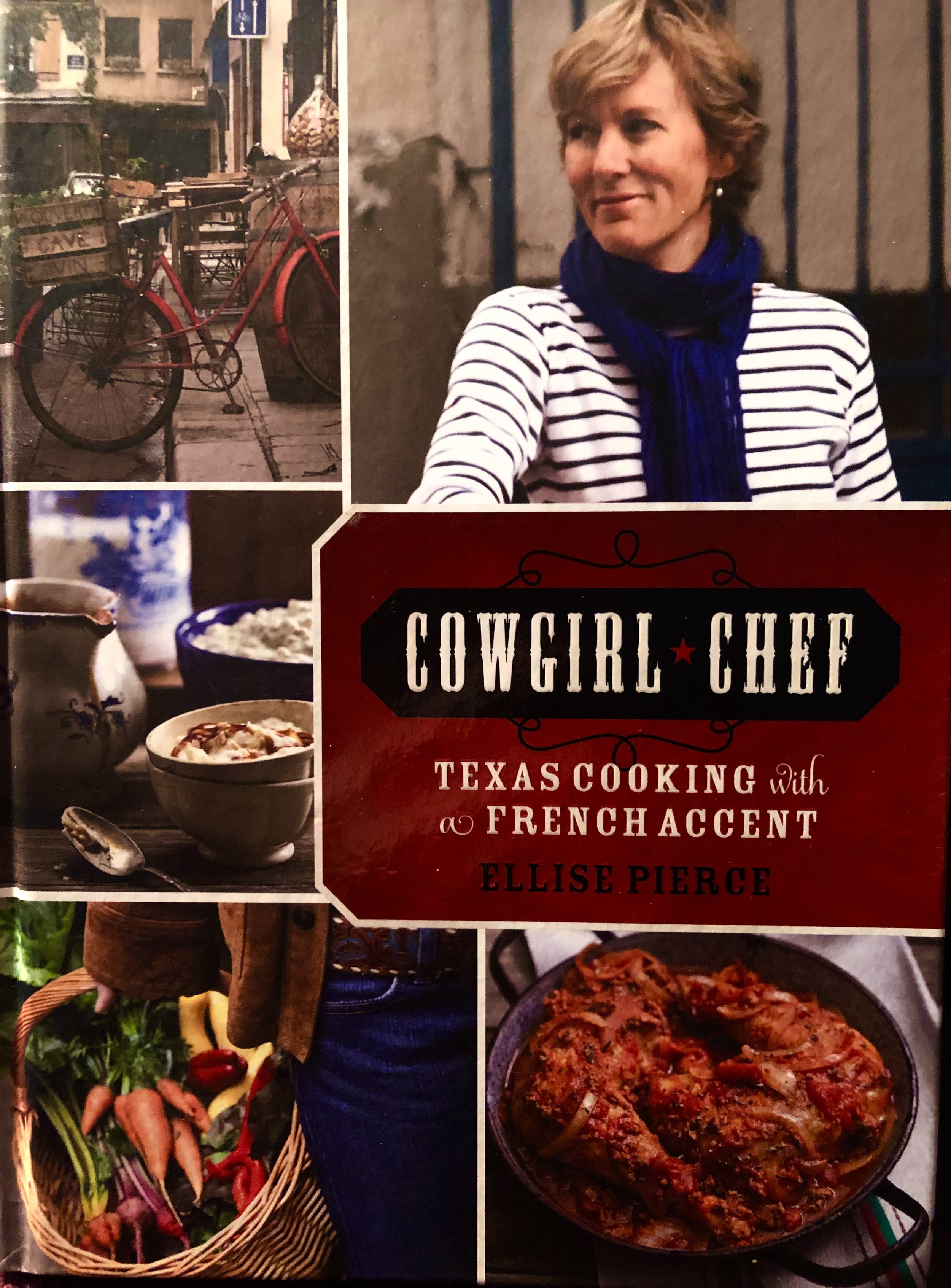

At Jefferson’s mention of Paris and food, Texan Ellise Pierce—author of "Cowgirl Chef: Texas Cooking with a French Accent"—kicks the conversation back to the present with her signature Texas boots. “Let’s eat, y’all” she says. “I’ve cooked a batch of cauliflower galettes with chipotle crème fraîche.”

“And for dessert, crème brûlée?” Jefferson queries with anticipation.

“Why certainly, Mr. President,” Ellise assures America’s first foodie. “Mais Oui!”