A Pioneer American Food Writer

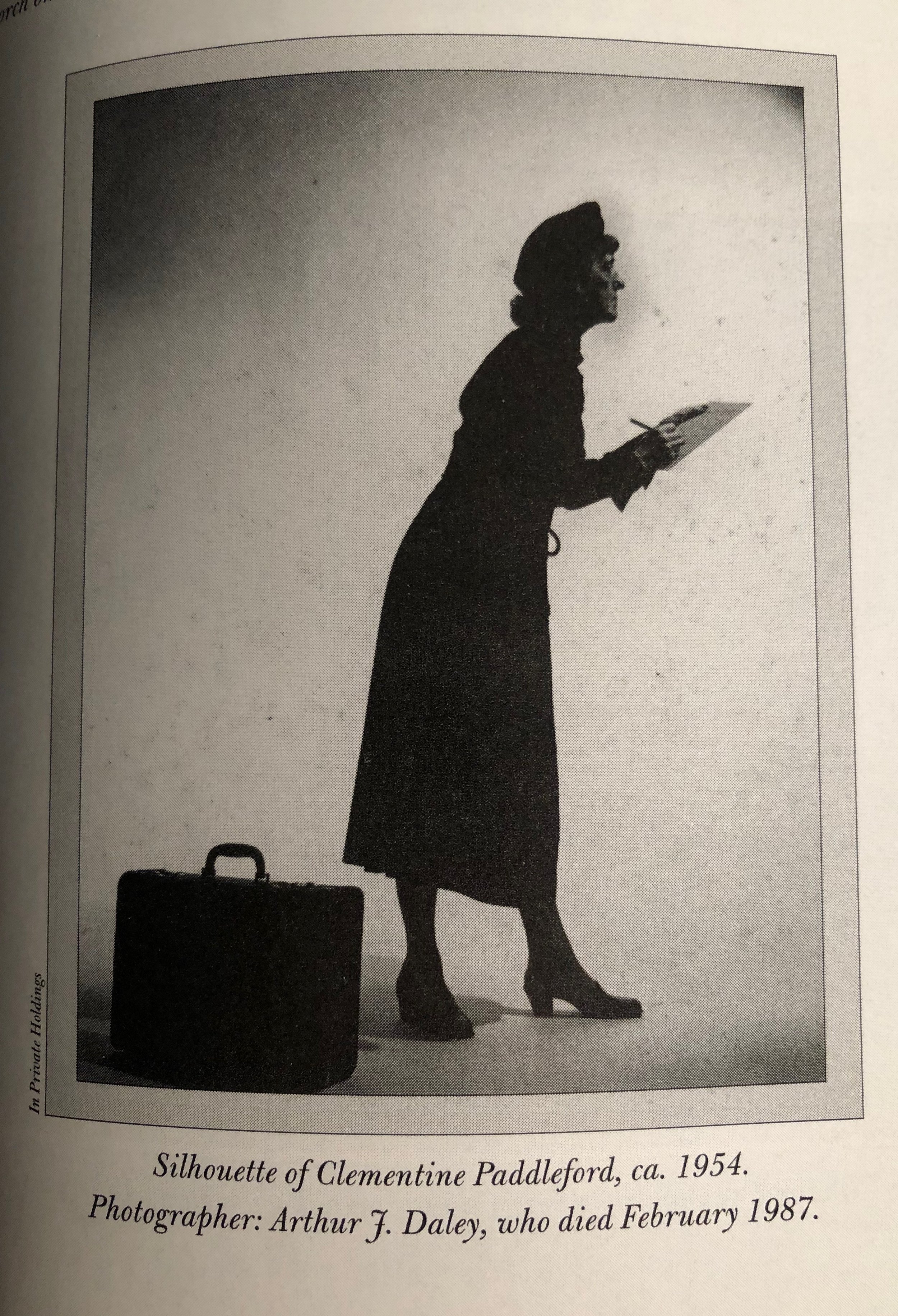

In November 2007, Saveur Magazine published a feature story about Clementine Paddleford—a pioneer American food writer who championed American regional cuisine from the late 1920s through the 1960s. I recall wondering at the time, “Clementine who?” Why had I never heard of this Nellie Bly of culinary journalism who crisscrossed the country for three decades, collecting recipes and stories in an effort to chronicle how America eats?

After reading the article, I was relieved to learn that I was not the only one asking that question. Kelly Alexander who wrote the article had never heard of Paddleford before her husband discovered a dusty copy of the food writer’s 1960 cookbook, “How America Eats,” in a used bookstore in Boston two years earlier. Intrigued with the author’s vivid descriptions of food, Alexander decided to learn all she could about the woman who revolutionized the art of food writing—America’s culinary “it” girl of the 1950s.

After convincing Saveur editor, Coleman Andrews, that Clementine Paddleford was worthy of a story, Alexander headed for Manhattan, KS. There she teamed up with Cynthia Harris, Kansas State University’s manuscripts/collections archivist. Working together, the two began organizing the voluminous body of Paddleford’s donated papers.

While virtually forgotten over the decades since her death in 1967, Paddleford was for a time perhaps the world’s most influential food writer. Born in 1900 on a 260-acre farm near Stockdale, Kansas—the same year my grandmother and Queen Elizabeth’s mum were born. Clementine Haskin Paddleford graduated from KSU in 1921 before moving to the other Manhattan to study journalism at New York University.

For three decades, this single mom who adored cats and piloted her own Piper Cub plane while doing research almost single-handedly defined how America ate. Her pet cat Pussy Willow accompanied her to work at the Herald Tribune and napped in the in-box on her desk. Her food column appeared weekly in the Herald Tribune from 1936 until the newspaper folded in 1966. Concurrently, she wrote for This Week, edited Farm and Fireside magazine, and wrote for Gourmet magazine from 1941-53. With an estimated 12 million weekly readers in 1953, she was called the “best known food editor” in America.

While Paddleford enjoyed covering international food stories behind events that included Queen Elizabeth’s coronation and Winston Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech in Fulton, MO, she also relished eating with crews on fishing boats and enjoyed sampling slum gullion at a Hobo Convention. She liked to boast that she ate “every dish at the table where I found it.”

Clementine attributed her love of cooking to her mother, Jennie who “stirred-in joy” and “seasoned every meal with love.” Her extensive travels—over 50,000 miles a year—taught her that “we all have hometown appetites.” “Every person is a bundle of longing for the simplicities of good taste once enjoyed on the farm or in the hometown they left behind.”

Such stories and wisdom were shared in crisp, smart prose that stimulated the senses of her readers. “Chowder,” she wrote, “breathes reassurance. It steams consolation.” To her, the perfect soufflé responded “with a rapturous, half hushed sigh as it settles softly to melt and vanish in a moment like smoke or a dream.”

“How does America eat?” asked Paddleford more than half a century ago. “She eats on the fat of the land. She eats in every language. For the most part, even with the increasingly popular trend toward foreign food, the dishes come to the table with an American accent.”

Paddleford’s cookbook “How America Eats” was based on personal interviews with more than 2,000 of the country’s best cooks who shared regional American recipes that are “word-of-mouth hand-downs from mother to daughter.” In addition to recipes, it documents the way immigrants influenced American cuisine—concocting dishes that had been “mixed and Americanized.”

In the foreword to Paddleford’s 1970 cookbook “The Best in American Cooking,” published three years after her death, a friend noted, “These regional recipes are a harvest of Clementine’s interviews, the windfall of her food reporting for over thirty years. Recipes carried in heads and in worn suitcases from lands around the world; recipes that fell into our national melting pot and emerged with a special flavor—American regional cooking.”

Following Kelly Alexander’s collaborative Paddlefordian research with KSU archivist Cynthia Harris, the two published “Hometown Appetites” in 2008. In the biography’s foreword, Saveur’s co-founder Coleman Andrews explained “Why Clem Matters.” Anderson wrote:

“As I started reading this obviously feisty, indefatigable Kansan’s reports (the recipes) from half a century earlier, I was seduced by their unpretentious tone and evocative detail, but I was also quite astonished. Though her writing was new to me, Clementine Paddleford had apparently invented Saveur Magazine when I was still in my highchair—not really inventing it, of course, but concerned herself with exactly the same culinary issues and approached her subject matter from exactly the same point of view we did.”

Thanks to “Hometown Appetites,” Alexander and Harris’s marvelous 2008 biography, Ms. Paddleford is back where she belongs: in the pantheon of pioneering American culinary journalists and food writers.