The Power of Words

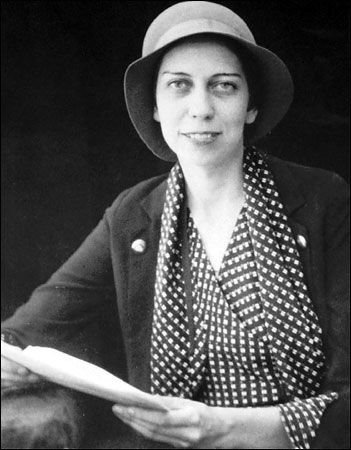

This April began with thoughts of Eudora Welty, grande dame of American letters. The acclaimed writer and Depression-era photographer was born in April 1909 in Jackson, Mississippi. The morning air is inviting on our deck surrounded by tall pines and firs in the Sierra Foothills—a million miles from the world of the American South that Ms. Welty captured in her stories and sepia-toned photographs. Squirrels and birds vie for my attention as I settle into the large rattan chair underneath the forest canopy with coffee and book in hand. It is a balancing act the writer would find humorous and enjoy acting out for friends.

I’d planned to go into my garden early, but find I want to know what shaped Welty’s early writing life. In her book, A Writer’s Beginnings, she talks of listening. Of hearing words as she writes. Of common things and what they come to mean over time. Of her fondness for New York City. And of her own special pulse on life in Jackson, MS where she lived for three quarters of a century. I remember now imagining a conversation with Ms. Welty not long before her death twenty years ago.

As I read her descriptions, her words resonate with common place scenes built upon across time, each layer a reflection of my own life as a gardener, essayist, and photographer. When I finally look up from her book to begin my morning walkabout in the gardens, Ms. Welty walks along with me. In a peaceful glade that has become a meditation garden, she asks for the story behind a Tuscan blue pumpkin perched like an aged sentry atop a pine stump. I tell her, the pumpkin survived unblemished throughout the fall, even when a winter storm buried it under two feet of snow in early January.

On a sunny March day, I photographed it. Unchanged. Resolute. Like the spirited population of Ukraine, brutally tested but still standing firm. For me, the pumpkin remains a silent reminder of courage and strength under fire. At one end of the pathway, I cut stems of lavender filled with purple flowers, enough to fill a silver mint julep cup my mother once gave me. Our walk takes us along a path of soft pine needles that cushion and mute our footsteps. Still, new beginnings can be seen and heard all around us. Irises, daffodils, pussywillow, camelia, and columbine as blue as the Pacific reach for dappled sunlight. As I listen to the silence, I am moved by the beauty of experiencing the day unfolding around me.

There were so many questions I wanted to ask Ms. Welty. She’d graduated from the University of Wisconsin, studied a year at Columbia University in Manhattan, and had ambitions to become a published writer. Instead, she’d returned to Jackson in 1931 when her father was diagnosed with leukemia and remained there with her mother following his death. Though she took occasional trips back to NYC relating to her writing and photography, Jackson continued to be her home throughout the remainder of her long and productive lifetime.

Sitting on a park bench in the glade, I wondered how her photographer’s eye had instructed her writer’s imagination. In our imagined conversation, Ms. Welty would at this moment sip the cup of tea that I had poured for her, praise the apple cake I’d read was her favorite, and then settle comfortably into a reflection on her beginnings as a writer. She would do so as easily as she had once moved through the scenes in her photographs, each one capturing a time and place that no longer exists.

“My father gave me a camera when I was fifteen,” she began. “During the Depression, one of my part-time jobs was taking pictures for the Jackson Junior Auxiliary and writing for the Jackson State Tribune. In the early 1930s, I began documenting scenes I’d been born into and until then had taken for granted.”

As a white woman from a privileged family in Jackson, Ms. Welty’s photographs captured the lives of everyday laborers and African Americans with the same humanity that she later penned into her stories. Traveling around the Deep South with her camera two decades before the civil rights era, she said “I learned that life doesn’t hold still. Making pictures of people in all sorts of situations, I learned that every feeling waits upon its gesture. I had to be prepared to recognize this moment when I saw it.”

Taking a deep breath and slowly exhaling, Ms. Welty referred to the connection from her photographer’s eye to writing in words that she penned in her 1984 memoir, One Writer’s Beginnings. “These (gestures and moments) were things a story writer needed to know. And I felt the need to hold transient life in words—there’s so much more of life that only words can convey—strongly enough to last me as long as I live.”

This grand lady’s sense of place, photographic eye, and writer’s imagination continue to inspire conversation, real and imagined—the mark of a truly gifted storyteller. Were Ms. Welty observing today’s America of dangerously partisan politics and our divided Supreme Court, she would feel a connection to Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson—President Biden’s gifted, supremely qualified judicial nominee, poised to becoming the nation’s first African American woman to serve on the United States Supreme Court. Ms. Welty would recognize and celebrate the possibility that if confirmed, Judge Jackson’s words might in time inspire her colleagues to see the world in a different way.