Still as Stone

This brilliant March morning, snow still as stone has fallen on our world in the Sierra Nevada Foothills. I carry a cup of cardamom chai tea to the small red kitchen table where I look out on birds, squirrels and two deer harvesting seeds and nuts along our meditation path. Before long, my thoughts travel from the wintry scene outside to other places connected across time. As if carried across a spinning Google Earth globe, I zoom to a hilltop in the Santa Monica Mountains in west Los Angeles. There, California sunlight reflects off the white stone façades of the Getty Center’s monumental structures.

Several weeks ago, I shared a conversation with my longtime friend Pat who moved to L.A. with me in 1974. On one of our early explorations of the city, we visited J. Paul Getty’s exquisite museum in Malibu designed as a Roman villa to house the billionaire’s collection of Greek and Roman antiquities. The collection which also included European paintings, French decorative arts, and photography quickly outgrew the villa’s capacity to display its treasures.

So in 1983, the J. Paul Getty Trust purchased more than 700 acres in the chaparral covered foothills of the Santa Monica Mountains above the 405 Freeway that connects west L.A. with the San Fernando Valley. A year later, architect Richard Meier began plans for a six-acre campus that would provide a unique cultural resource for a Los Angeles museum, art and photography galleries, and facilities for the Getty’s education and research programs. When the Getty Center finally opened in December 1997, it instantly became an architectural landmark for the city where Kit and I met in 1977.

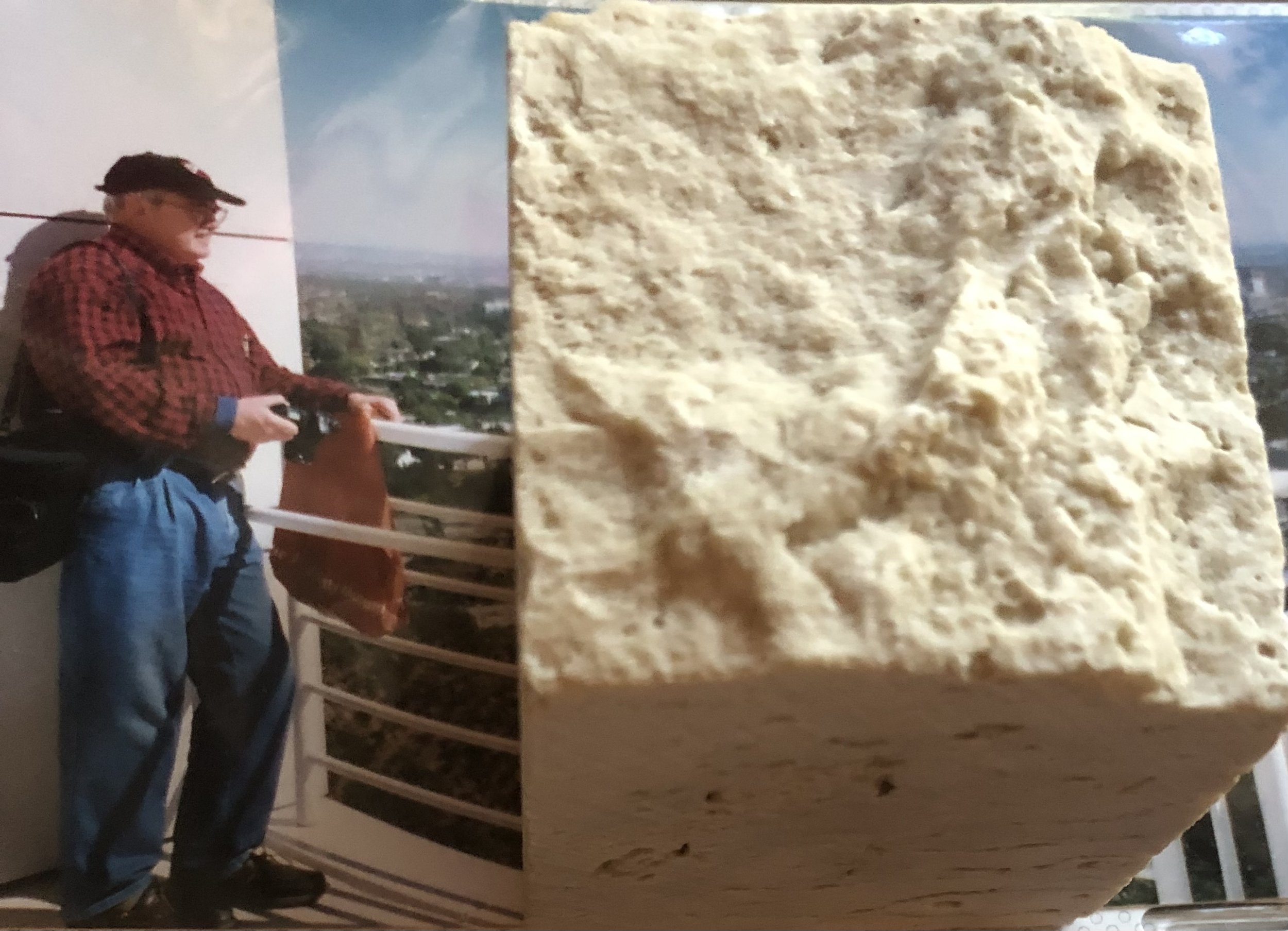

Back in the Sierra Foothills, my thoughts then drift to façades and pavements created from 300,000 pieces of travertine from a quarry near Rome. Travertine formed from mineral-rich springs 8,000 to 80,000 years ago. Crystals accumulating in layers like the granular snow outside my window. Stone aged into hardness, hiding for centuries and millennia the impressions of leaves, a feather, and a deer antler. Ancient fossils revealed on the edge of a new millennium as 20th century masons split the transported travertine along the grain of the stone to the Getty Museum site.

The world of art and architecture has been an integral part of my life with Kit. When he was teaching at UCLA, he walked a geography field class through a Santa Monica neighborhood where he spotted a California bungalow on 2nd Street wrapped in chain link and corrugated metal. Ever curious, Kit knocked on the door. The owner and designer of the house answered the door, and an energetic conversation transpired. The man turned out to be none other than the soon to be world-renowned architect Frank Gehry.

From that small experiment with chain link in Southern California, Gehry gained international status as an architect and has continued to produce structures that surprise us. His architectural masterpiece in Bilbao, Spain leaves visitors trying to describe it and many surrendering to metaphor. To some, it is “an enormous bouquet of writhing, slippery-skinned silver fish.” To others, it is “a leviathan sheathed in mirrors” or “a mermaid sprawled along the river, hair blowing in the breeze.”

This 5,000-ton, steel-framed, titanium-wrapped structure seems to rebel against regular form, recreating itself like a whirling dervish with no regard for known architectural conventions and rules. Architect Philip Johnson declared it “the greatest building of our time.” Another critic sees it as “Frank Gehry at his best…slightly out of control.”

Nature too is an architect of great beauty. My thoughts now return to the winter scene out my window in the Sierra Foothills where the stone-like surface of my icy meditation pathway reflects light with the same intensity as Gehry’s soaring, $100 million dollar titanium creation in Spain. Brilliant in design, Bilbao is as unique a vision of art on the landscape as the Getty Center in Los Angeles.

Finally, my thoughts travel back to our first country home in Missouri to a winter when it was so cold that the pond at Breakfast Creek froze up zipper tight and stayed frozen solid for days. I hadn’t skated since I was a child, but before long, a skating arty was assembled. Kit and Orion Beckmeyer edged out on the pond first. With snow shovels and a wide push broom, they swept clean an icy pathway wide enough for three skaters with arm’s linked to skate clear and free. Bundled up from head to toe, Orion’s wife Barbara, neighbor Diana Hallett and I laced up our ice skates and eased out onto the ice.

Before long, our feet and legs began to trust the firmness of the ice, frozen hard as stone. We had all grown up watching the Ice Capades and had striven to copy the dazzling star skaters’ graceful moves. Amazingly, none of us fell that day. Instead, we skated forward and backward in pairs and once emboldened, tried a few ballet-like moves on a single skate. Memory took over, and we were all skating with abandon as we had as children.

Snow still as stone unlocked these memories long frozen in time. Such is the power of nature. Such is the beauty of architecture. Such is the magic of memory.