Speaking of Noses

Recently Paul, a Peace Corps pal of mine from the late 1960s, emailed that he’d just had a four-hour skin cancer procedure on his forehead—one of many he has endured over the years. “We fair-skinned people pay the price for our vitamin D,” he wrote. When we were little, my aunt used to take me to the beach at Wildwood or Atlantic City, NJ. To get a good tan, she always had a steady supply of Johnson’s Baby oil spiked with a bit of iodine that was slathered over us. Funny, I never got tan, just lobster red.”

While Paul’s 30 stitches were healing, I shared a story about my own experience with skin cancer in 2004. It begins, “I wonder if there’s a book on the subject of noses. Let’s face it, the world is graced with noses of every size, color, and shape imaginable—one affixed to every creature on the planet. Hooked, flat, button, pug, noble, straight or broken, your nose is your personal punctuation mark prominently positioned front and center, a step ahead of the rest of your body as you move about in the world.”

The nose is a sensor, an olfactory guide to the world’s garden of earthly fragrances. I rub the stems of two common herbs and release the lemony scent of thyme and rosemary. Tall feathery dill and anise fronds offer their own distinctive tastes and smells. Lavender says Provence and lemon grass Bangkok—each fragrance a delicate essence that evokes a place that is part of my past.

By nature, noses react powerfully to extremes and excesses. When ingested in big doses, nutmeg, ginger, cinnamon, and cloves can turn the nose red, just as a warm red wine, pollen or a nasty cold will. And as Paul has reminded me, the worst enemy of fair-skinned folks like the two of us is cumulative years of exposure to the sun.

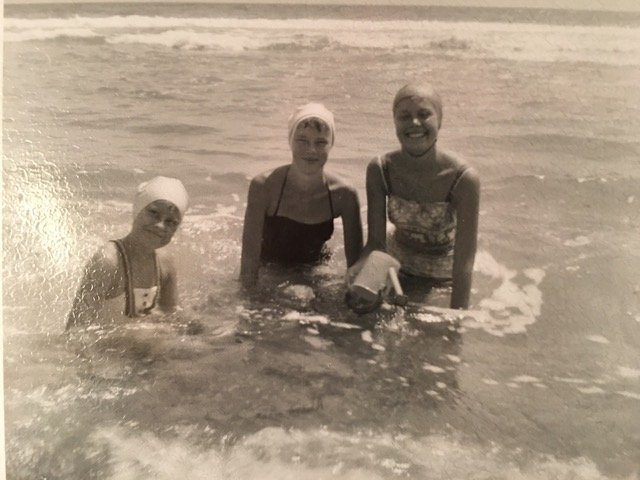

Growing up in Texas, my sisters and I lived outdoors, spending much of each summer perfecting our dives and tans at the local swimming pool or during summer trips with our parents to the beach. We were fearless freshwater fish by the age of four, basted with Coppertone from top to bottom to keep us from burning. My sisters emerged from their summers in the sun brown as berries. I was the fair-skinned, freckle-faced exception in the family of otherwise beautifully tanned bodies. For this reason, my bag of swimming gear always included a tube of zinc oxide to protect my nose from peeling. In pictures of our local swim team, I am the fish with the glaring white nose.

Because the damage was done all those innocent years ago, I came face to face with a diagnosis of a basal cell carcinoma in 2004, circling like a shark below the sun-abused skin on one side of my nose. Treatment required more than a hit of liquid nitrogen that burns off pre-cancerous growths on the skin. Positive biopsy results led to a referral to the hospital’s Cutaneous Micrographic Surgery Clinic. At 8:00 the morning of my surgery, my nose was numbed, my eyes covered, and a glaring light pulled down directly over my face.

By noon, four scrapings of skin had been excised and biopsied—a scary long time to focus on how I felt about my nose. It wasn’t straight or elegant like my three sisters’ noses, but more like Dad’s after his was broken playing football. Those zinc oxide summers, having freckles, my tendency to blush when called on in class—were they all connected? Who knows? Blame it all, as I did throughout my youth, on my less than perfect nose.

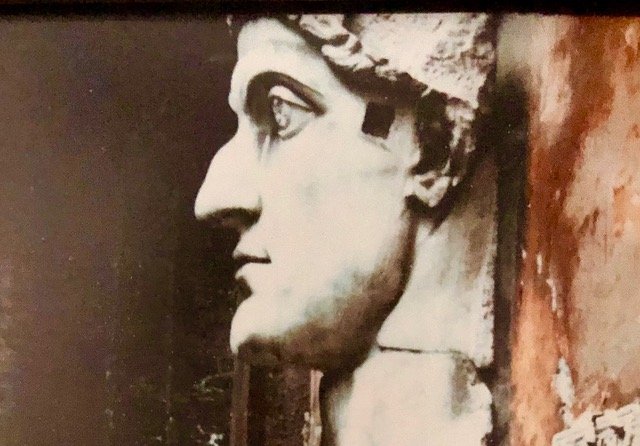

Then a trip to Rome forty years ago opened my eyes to the classical proportions of European noses. In a tiny alley near the Coliseum, Kit and I discovered a wall covered with fragments from ancient Roman statues—arms, heads, hands, and nearby, a giant stone nose mounted on a pedestal. At that moment, I turned my profile to Kit and handed him my camera. As I stood next to that noble Roman nose, he captured the moment for posterity.

“You have a beautiful nose,” my doctor told me that afternoon as he studied my face intently and mapped out his surgical strategy. “Lots of contours.” While he worked his magic, we talked of roses, romance, an apple orchard he lived near in Korea where he’d been born 37 years earlier, and how I came to appreciate the unique nature of my nose while exploring Rome.

“I’ve operated on over 2,000 noses,” Dr. Yoon added finally, “and each one is different.” Then he covered my eyes again, patted me on the hand to let me know he was there, and whispered, “Yours won’t be perfect, but it will still be beautiful.”

Reassured, I retreated peacefully into that little alley in Rome where grand noses, even when imperfect, are viewed as works of art to be treasured and preserved through the ages.