Passage in the Desert

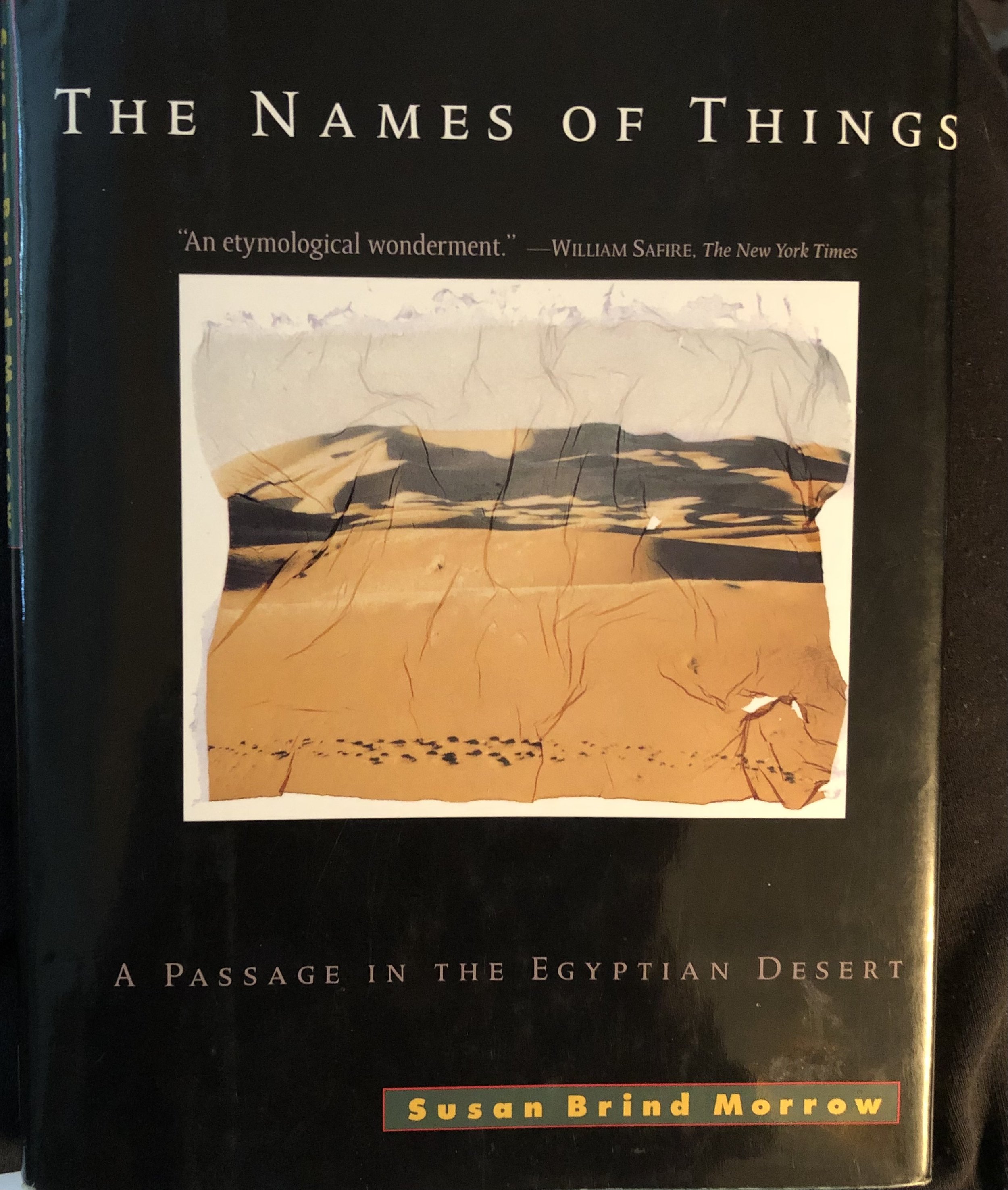

Recently my friend Phyllis wrote that for some reason she had been compelled to read a book on grieving. A friend of hers had sent the book to her after her father died. Phyllis had glanced through it, then all of a sudden started reading it. She still grieves the loss of both of her parents. Knowing that it helps to read how others deal with such feelings, I told her about Susan Brind Morrow’s memoir The Names of Things. It is about words. About memory. About loss. And about a journey the author took into the Egyptian Desert to deal with grief.

I’ve just shared with Phyllis the following essay that I wrote in 1997 after reading Morrow’s magical book—

The Names of Things

I’ve been on a literary journey recently to a place I’ve never been, but now feel that I have. That’s the power of words and the magic of The Names of Things, a book that recalls author Susan Brind Morrow’s years spent tracking the ancient roots of language in Egypt in the 1980s. Part memoir, part travel journal, part commonplace book, part etymological treasure-hunt, the book is a passage to the Egyptian Desert--a world as old as time.

My journey with her to Egypt’s Desert, the Sinai, and the Red Sea was a tutorial in ancient hieroglyphics and finding the origin of words in nature. Sacred words like flags that mark tombs, rocks, and trees in the Egyptian desert even now. Ancient words that began as a description of a living thing when the land first became desert, carrying the thing concealed across the millennia.

“But the original, the thing itself,” Morrow writes, “would never come back. It had passed away from the world. You could conjure it, though, the emotion that kept it alive inside you, with a trigger: an image, a smell, a combination of sounds that formed it into a picture that stayed in your mind. That was the life of the thing after it died. The only thing that could bring it back. That is what a word is worth.”

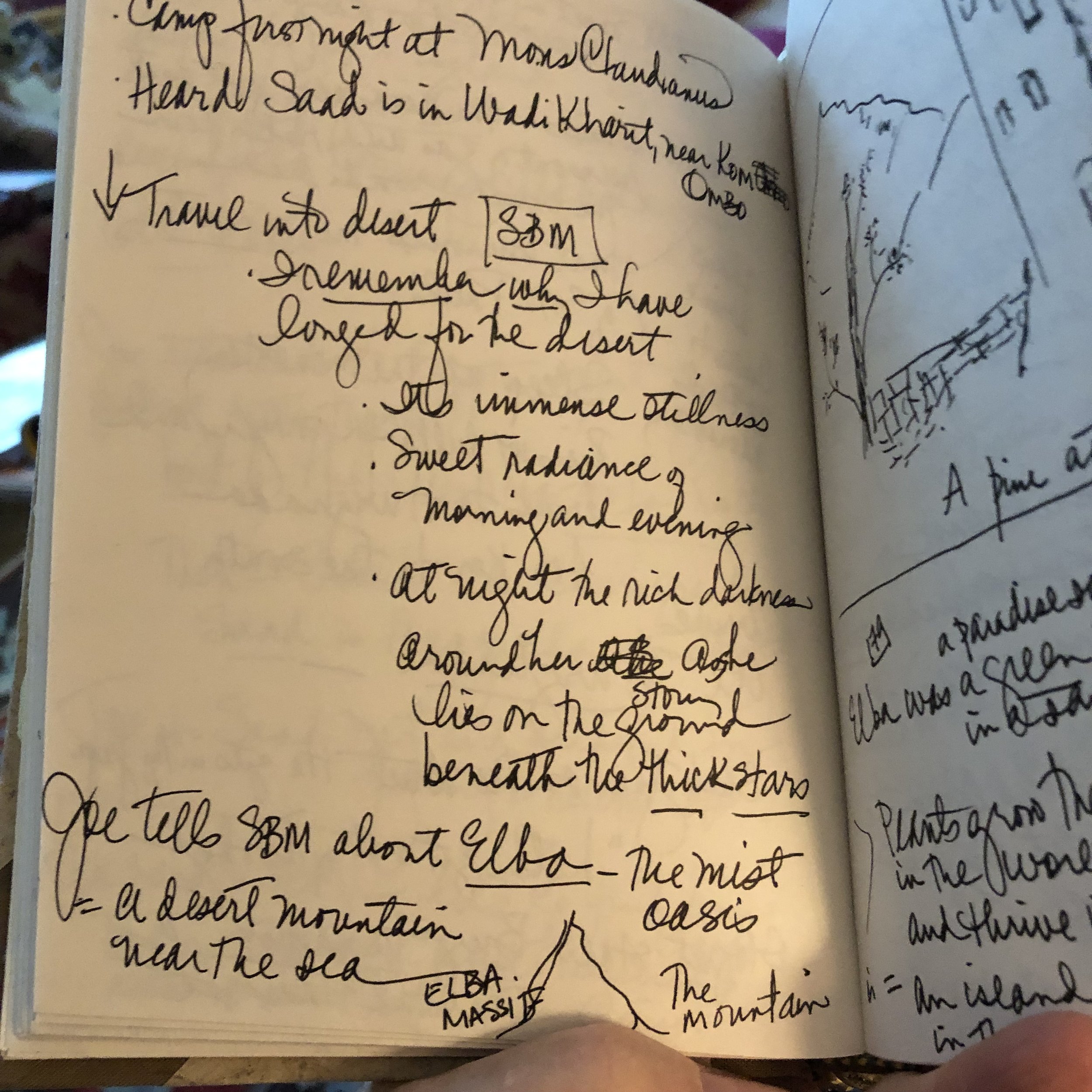

As I read Morrow’s descriptions of her childhood in upstate New York, Cairo’s chaotic streets and alleys, favorite words remembered and new ones discovered during her passages in the desert, I began a journal of my own mirroring her own journal, needing to physically form her words myself with ink on paper. “Nile, Egypt’s sweet sea.” I transcribe from Morrow’s notes, “once clotted with papyrus, thriving, gigantic, mobile, filled with bird and animal life as today it only is in the Sudd—a great marsh in South Sudan.”

Papyrus. A plant that no longer exists, except in a dead language--the hieroglyph green. Environmental extremes in Egypt are defined with colors. The desert is red. The sea is green. Morrow becomes my teacher, just as Steele Commager was her teacher at Columbia University. “He loved words,” she recalls, “had us track things, word origins, poetic lines.”

Traveling with her into the harsh openness of the desert, I imagine walking barefoot in the sand and dive into a dune, feeling the warmth around me. She warns, “it takes time to learn that refuge in the desert is at best temporary: a shrinking line of shade, the coolness of water or the dark. In transient things like song or conversation.”

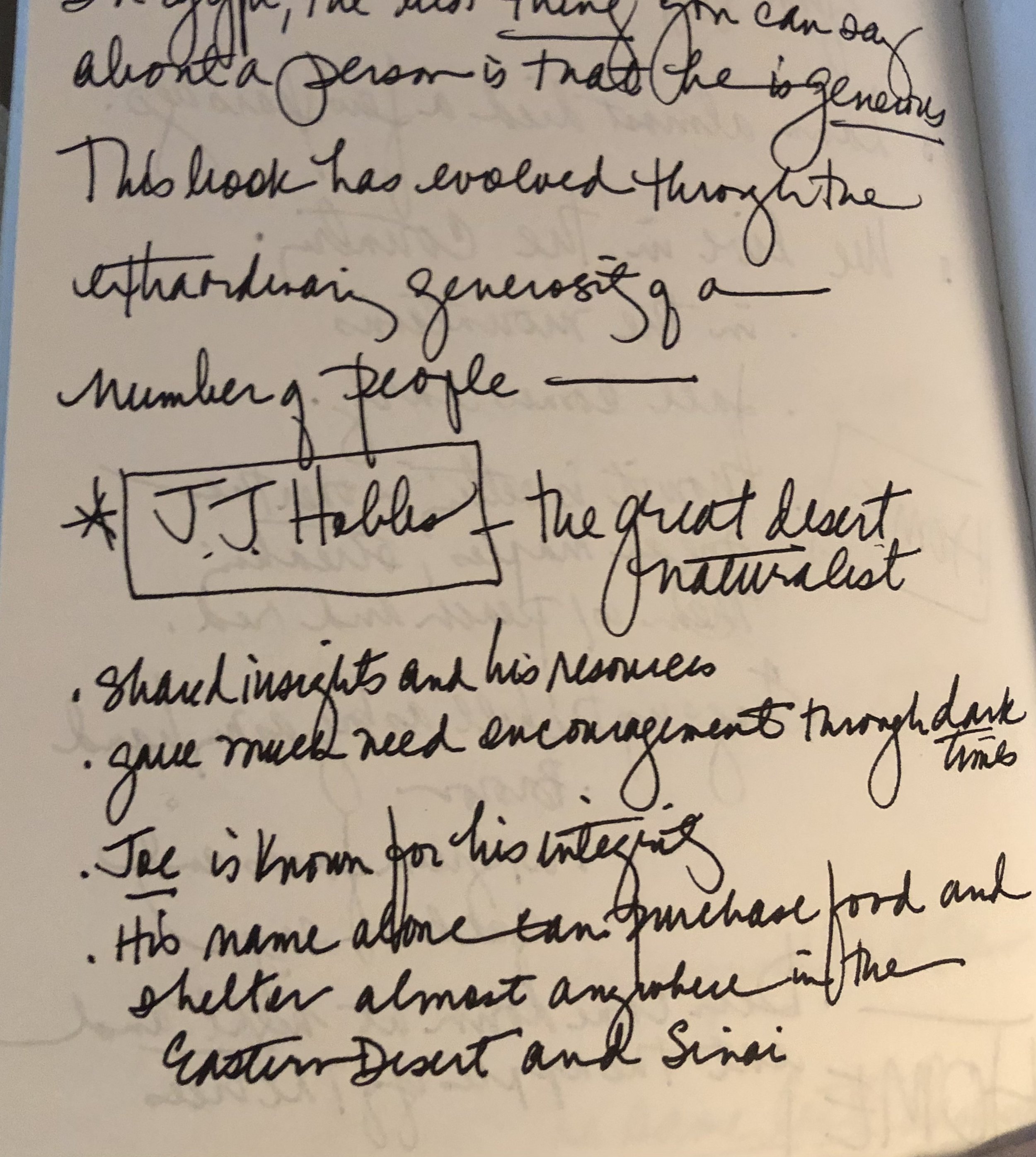

Together, we explore starry skies that she studied as a child and revisited in Egypt’s deserts where she travels with nomads and her guide, Joe Hobbs—a University of Missouri-Columbia geography professor who she acknowledges as “the great desert naturalist…known for his integrity. His name alone can purchase food and shelter almost anywhere in the Eastern Desert and Sinai.”

Joe is my friend as well. We share a love of cats, lizards, birds, tortoises, stars, storytelling, maps and curious creatures. Who else, I wonder, has explored the Egyptian desert wadis and roads known to Joe and Susan? Are there maps of the landscape and sites that they visited?

An editor friend at National Geographic replies to my query that little has been published in National Geographic about the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Another friend sends David Rumsey’s historic map website where I discover a wealth of historic maps of this region drawn by cartographers from as early as 1742.

I am reluctant to leave Susan Brind Morrow’s book and put away historic maps that orient me in this desert world of shifting sand, rock worn by harsh winds, and borders that resist the idea of nations. The names of things. Maps—lines traced by the feet of past explorers. These things have been invaluable companions on my literary passage in the Egyptian Desert. (1997)

Back in the present 27 years later, I am in awe of Morrow’s personal and literary journey. In today’s hyper-charged world filled with noise, stress, disinformation, and politicians gone weird, there are moments of staggering sadness that can leave us feeling lost. The Names of Things is worthy of revisiting. Morrow’s slow study of words and the power of memory serve as reminders of the quiet freedom she experienced during her passage in the Egyptian Desert that helped her come to terms with her own grief.