On the Timeless Subject of Words and Family

Language has the power to connect us over distance and time. In a biography of John Adams, I came across a quote by Thomas Jefferson— “The earth belongs in usufruct to the living.” A reader with any modicum of curiosity could not sail through such a sentence without backing up to chew awhile on the odd, antiquated, mouthful of a word that holds the key to Jefferson’s meaning. Us-u-fruct. So, I did.

I then went to my library shelf and pulled out David McCullough’s biography of Adams and turned to page 450 to remind myself of the context of the word’s usage.

McCullough had been talking about a correspondence between Adams and Jefferson in the spring of 1794—the first in two years.

The two had had serious differences with each other but it was spring. Jefferson had returned to Monticello and returned to farming “with an ardor,” he wrote to Adams, “which I scarcely knew in my youth.” Adams, who spent summers at his farm in Quincy, MA whenever possible, agreed and wrote back of a summer “spent so deliciously in farming that I return to the old story of politics with great reluctance.”

McCullough notes, Adams disagreed with his friend when Jefferson observed that the “paper transactions” of one generation should “scarcely be considered by succeeding generations,” that “’the earth belongs in usufruct to the living’: that the dead have neither the power nor rights over it.” Jefferson, McCullough explains, was writing of a principal that Jefferson believed to be “self-evident.”

At this point I turned to my dictionary for more on the subject of “usufruct.” Its Latin root is “usufructus.” In legal jargon, it refers to “the right to utilize and enjoy the profits and advantages of something belonging to another so long as the property is not damaged or altered in any way. Use and enjoyment.”

It was a time of building revolutionary fervor in France. Jefferson felt “a little rebellion now and then to clear the atmosphere,” was a good thing. Adams, McCullough observed, “refused to accept the idea that each generation could simply put aside the past…to suit its own desires.

Unspoken in these letters were Adams’ suspicions of what Jefferson’s “retirement” to Monticello would do to him. Jefferson much later acknowledged in a letter to his daughter Polly that during the period from 1793 to 1797 when he withdrew from the world of politics to his mountaintop at Monticello, he’d suffered a breakdown that left him “unfit for society, and uneasy when engaged in it.”

I think of these two founding fathers—one a frugal New Englander, the other who designed a French villa atop a mountain in Virginia—and marvel at the enduring documents that reflect the combined legacy of their ideas and words. I am also fascinated with the nature of their friendship built around letters. Adams, according to McCullough, understood Jefferson. And though politics severely tested their friendship for a period, the two men corresponded regularly in the final years of their lives, sharing their thoughts once again as old friends.

On a 2006 trip to Madrid, Kit and I visited our son Hayden, his wife Ana, and their three young children—Nicolas (9), Ines (4), and Catalina (2). Hayden had by then lived in Europe off and on for 15 years was fluent in Spanish. When called upon in professional situations, he relied on the French and Italian he picked up while living briefly in those two countries before settling in Spain.

At the time of our visit, Nicolas spoke in animated English with us about soccer and quoted favorite scenes from the quirky American movie “Napoleon Dynamite.” Conversations between Hayden and Nico moved seamlessly from Spanish to English to French. Nico had also picked up Portuguese from Vera—a Brazilian woman who had lived with the family since Nicolas was five.

Ines was a charming and affectionate four-year old, eager to know her American abuela and abuelo. Fixing her enormous brown eyes on my face, she touched my mouth and hair, and then waited for me to speak. Unfortunately, her English was limited and spoke no Spanish. Desperate to communicate, I realized that our common language had to be French—the language Ines was using at the Madrid Lycée Française, and I had last studied in high school decades earlier.

“Rouge,” I said, touching the rosy color on her beautiful face. “Red.” Then reaching into my purse, I pulled out a compact and brushed her cheeks and nose with a touch of plum-colored powder.

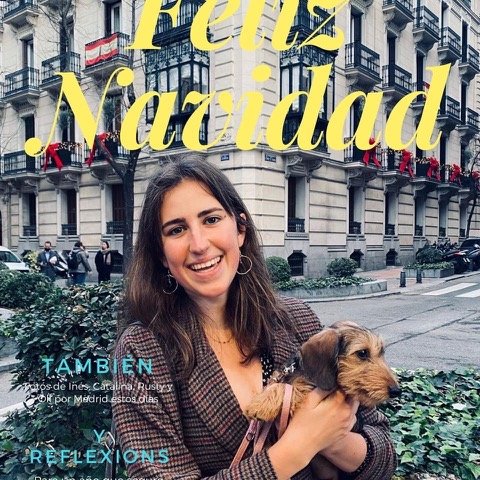

From that moment on, French—however basic and rusty—connected us heart to heart in that magic way that only language can. For Ines, I became abuela Cathy. Last week, Ines turned 20. Currently a freshman at Stanford University, she is a beautiful young citizen of the world, traveling with ease from Europe to Asia to America, fluent in Spanish, English, and French. On the subject of language and life, our beautiful granddaughter Ines, is clearly a superstar!