On Assignment in Manhattan

As I was watering the gardens at our home in the Sierra Foothills this morning, two wonderful neighbors appeared on their morning walk with their two wire haired fox terriers. Tim grew up in North Central Kansas. Terri grew up in New York’s Hudson River Valley near West Point. Known affectionately by their local dog-loving friends along our road as “Tim, Terri and the Terriers,” they remind me of what makes NYC and Manhattan work as an urban experiment.

Like our world in Nevada City, CA but on a mega scale, NYC is a collection of a thousand diverse neighborhoods where the noise of the world and cultural differences fade away at the end of the day. When Terri visits NYC as she will this week, she visits her two sons who share an apartment in the Astoria neighborhood in Queens—a multinational borough where diversity is key to harmony. Upon learning of her upcoming trip, I recalled an assignment that Kit and I were offered by National Geographic in the middle of winter almost thirty years ago.

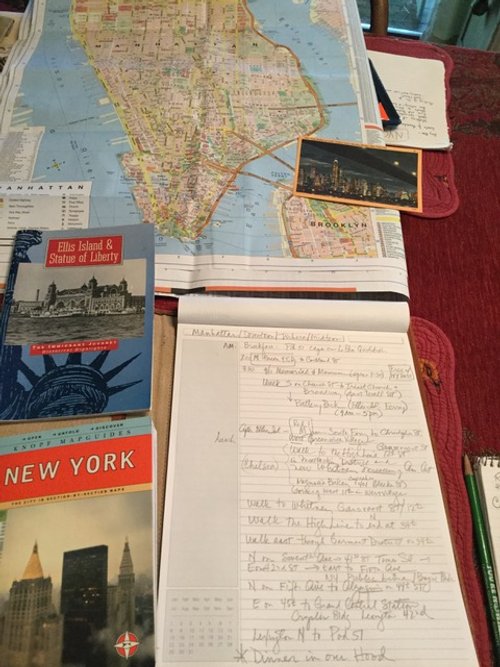

In February 1994, the two of us found ourselves on assignment in Manhattan. We were to scout a four-day field walk for forty teachers who would be attending an urban institute that summer in Washington, DC. We loved maps and urban exploration and it sounded like old hand. For ten years we had organized urban field walks in Washington, DC during the month of July as part of a National Geographic Summer Institute program for teachers from around the country. Of course, we immediately said yes. Never mind that we knew next to nothing about Manhattan. As two geographers afoot in one of the greatest cities on Earth, we’d figure it out after a little fieldwork. Piece of cake.

Our task was daunting. Our assignment was to fly to Manhattan, scout the city over the course of three or four days, and somehow deconstruct the maze that is Manhattan. I remember asking myself how a person who hasn’t lived in New York City ever learns to navigate the island of Manhattan? How does one ever understand the amazingly dynamic and complex nature of its geography?

It’s one thing to view Manhattan from the window of a speeding yellow taxi, never quite knowing where you are as your driver weaves through dense, cross-town traffic on route to your conference hotel or to some fabulous neighborhood restaurant a friend recommended. It’s quite another to lead a band of forty urban geography teachers throughout a densely constructed and populated metropolis on foot and by subway and bus. That was the daunting task Kit and I faced when we arrived in Manhattan that February, the day after a wintry snowstorm.

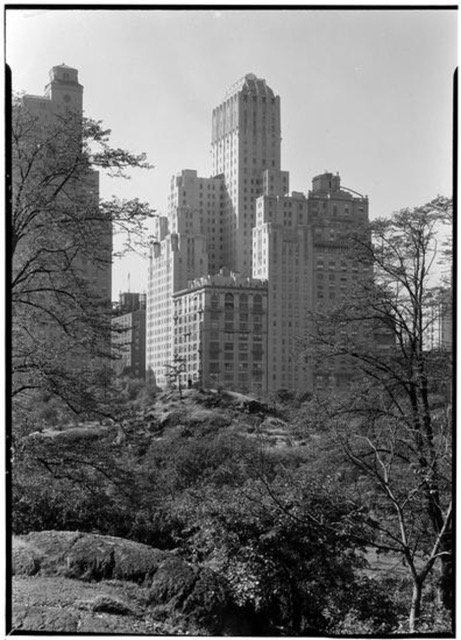

NGS put us up at the once elegant Barbizon Hotel, a 23-story landmark, located in Manhattan’s posh Upper East Side at Lexington and 63rd Street. Built in 1927 and on the National Register of Historic Places since 1982, the Barbizon is a blend of Italian Renaissance and late Gothic Revival architectural styles—an imposing steel framed structure encased in concrete, faced in salmon-colored brick with limestone and terra cotta Islamic inspired decorative elements. As monumental as an Aztec temple, it was considered a “safe retreat” for women only residence hotel, boasting a list of famous residents and guests that included Lauren Bacall, Joan Didion, Grace Kelly, Sylvia Plath, Eudora Welty, and my mother Alice.

Unfortunately, the famed Barbizon was on its last leg the night we arrived. Dispirited after being issued keys to five different rooms, only to find each of them already occupied, we at last came to rest in a room the size of a service elevator. This did not bode well, but a delicious breakfast of French toast with strawberries and hot coffee the following morning got us into the proper mood to tackle our assignment.

“We have to walk from this hotel to the tip of Manhattan,” I said to Kit. “That’s the only way we’re going to experience the city’s neighborhoods, districts and transportation links the way New Yorkers do.”

And that is exactly what we did. Whenever Kit and I visit NYC, we retrace the same neighborhoods, districts, parks, and squares on foot, much as we did earlier. And over the years, we’ve added walks that were new territory for me—across the Brooklyn Bridge, along Manhattan’s High Line and within Central Park.

All those years ago, Kit and I had literally walked Manhattan until its map was etched in our heads. Once you see the city as a collection of neighborhoods filled with people and their histories, you understand the weave of its fabric. It ceases to be lines on a one-dimensional map that you see from the back seat of a taxi.

Once oriented, your feet hit Manhattan’s pavement and you become a part of the human energy flowing through its network of streets and avenues. Like the city, you feel alive and are rarely lost for long.

That’s what we taught those forty high school teachers back in 1994 when we turned them loose and showed them how to explore a city. Not one of them got lost, and hopefully, they returned to their classrooms and shared the magic of geographic exploration in their own cities and neighborhoods.

Cities are alive with stories. Geography gives you the tools to read urban landscapes and explore the stories that cities have to tell.