Ella and the Great Blue Heron

February was a hard month. Frozen and bitter cold. We are all coping as we can here in Missouri, coming up with creative ways to keep animals and chickens warm. Recently, Boone Countian Diana Moxon posted a picture on Facebook of one of her elderly hens roosting on a nest in her bathroom. The image made me smile and reminded me of a drama that involved my favorite goose Ella from our days at Breakfast Creek. What follows is that wintry tale retold.

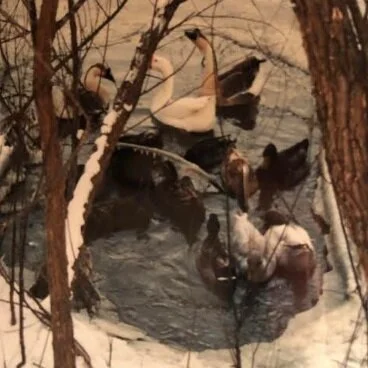

Early one frigid morning, I came upon a great blue heron lost in dreams of soft water. We had both come to a spot along the western edge of the pond that was the last place to freeze in the night. The heron had seen two geese and a small paddling of ducks circled around what looked like an opening in the ice. But sometime in the night, the mischievous old moon had reached out its icy fingers and pulled the pond's zipper tight, leaving them to deal with the frozen elements on the coldest night they have known this winter.

It isn't easy to surprise a heron. Silent and stately in their movements, they hunt for food alone. So glacial are their movements as they wade around the edge of a pond, herons often appear to be asleep. In reality, they see all. Pencil-thin and periscope sharp, they ever so slowly investigate the possibilities that move beneath the pond's surface. Fish, frogs, and other small pond creatures quickly fall prey to the lightning-fast spear motion of their long, pointed bills.

But the night before, winter had showed its mean streak and made the search for food hard. Made everything hard, most of all the pond itself. To stay warm, the heron reduced itself by half. Facing rearward, the solitary fisher bird had periscoped its neck down into itself and tightly tucked its great head and bill into the downy warmth of its own wing. By morning, all that appeared to remain was a cold blue shadow balanced on a single stick frozen fast onto the ice.

The heron had rendered himself invisible and drifted into a deep sleep. That particularly cold night, he didn't mind being alone. Perhaps he was remembering the soft feeling of warm water against his long, spidery legs, and the silken feeling of pond muck between the digits of his thin, birdlike feet. In that dreamy warm-water port, he floated through the hours until dawn and was still a thousand miles away when I stepped out onto the ice.

At that instant, the steel-blue shadow frozen to the ice lifted upward with the drama of Arthur's Excaliber emerging from the stone that had held it captive for mythical ages. In the flash of a second, we saw each other and were both amazed. The heron, because he is rarely caught sleeping. The intruder, because I had never witnessed a heron's movements from so close a distance. For a moment, the great bird seemed to hang in the frigid air while his long spindly legs unfolded, and he arched his long neck downward into his shoulders. Finally, in the curious posture of heron flight, he lifted upward with the quiet power and grace of a Concorde jet, banked slightly westward, and flew off into the cold morning.

That winter, only four of the original gaggle of twelve geese remained. Each winter I’d lost a goose to either predators or stress related to some trauma they had experienced. Their naturally aggressive nature had led me to feel confident about their ability to protect themselves. But Winter was about to remind me how hard living in the wild can be.

Late in the afternoon, I walked to the pond to see if I needed to widen the opening on the ice for the ducks and geese. After testing my weight on the ice, I inched toward the opening and pounded at its edges with a shovel, sending the nervous cluster of geese and ducks scrambling for safety on the ice--all except for my favorite goose Ella who seemed to be sleeping.

I then noticed she was bobbing up and down among the ice chunks that congested the tiny opening. Stepping cautiously back on the ice, I reached into the icy water until my arm had a hold of Ella's underbelly. There was no resistance, a certain sign that she too understood the gravity of her own situation. Her body had stopped producing the critical oils that make her feathers buoyant in water and maintain her body's warmth in freezing temperatures. Ella was literally freezing to death.

Within minutes I’d scooped her out of the water and wrapped her in a large towel. For the next week, Ella slept in our sunroom on a bed of straw with a bucket of water and a pan of cracked corn.

When she began to revive, I carried her to our bathtub and stood her in warm water. Gradually, she began preening and splashing water on her back Finally, with her neck craned backward, she began spreading the oil now flowing again from a tiny hole in her back until she’d coated her feathers. The other geese were ecstatic when I finally returned her to the pond. I can only imagine the stories she told them of the day the pond froze over, and she bathed in a bathtub up in the big limestone house at Breakfast Creek.