Brave the Wild River

On March 20, 2024, President Joe Biden issued an executive order instructing the National Park Service to “highlight important figures and chapters in women’s history.” “Women and girls of all backgrounds have shaped our country’s history, from the ongoing fight for justice and equality to cutting-edge scientific advancements and artistic achievements. Yet these contributions have often been overlooked. We must do more to recognize the role of women and girls in America’s story, including through the Federal Government’s recognition and interpretation of historic and cultural sites.”

Serendipitously, I just finished reading “Brave the Wild River: The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon.” It is a riveting tale of two legendary female botanists and their historic 1938 boat trip down the Colorado River and through the Grand Canyon. Their pioneering work in charting the social and environmental landscapes they traversed is meticulously researched by science journalist Melissa L. Sevigny.

In late July that hot summer, Dr. Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter joined a motley crew of four boatmen on a daring forty-three-day adventure that took them from Utah to Nevada through 660 miles of perilous terrain. For the men, the journey was about running the Colorado River and coming out alive. For the two women, it was an expedition in pursuit of science. Clover who worked at the University of Michigan as a botanist had already collected may native species, particularly cacti, on prior expeditions to the American Southwest. Jotter, one of her former graduate students, had previously worked as a National Park Service naturalist.

Before 1938, there was no record of a woman successfully traveling down the Colorado River. Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter became the first women to successfully make the trip. Despite their differences in personality and 17-year age gap, the two women were united in their scientific mission to collect and identify as many plant species as they could throughout the inner canyon of the Colorado River. In her journal penned during the expedition, Clover wrote, “This part of the West is inaccessible because of a complete lack of roads and trails. It has never been explored botanically and for that reason everything collected will be of interest.”

Sevigny’s terrific book reminds readers that the story of the Grand Canyon has been etched out into its geological layers over time. The NPS points out that “the intricate stories of its flora were largely ignored by the academy until the painstaking and boundary-breaking work of the two female botanists in the summer of 1938.” Their bond was their shared passion for botany along with their physical strength and willingness to persevere when parts of the trip were strenuous and dangerous.

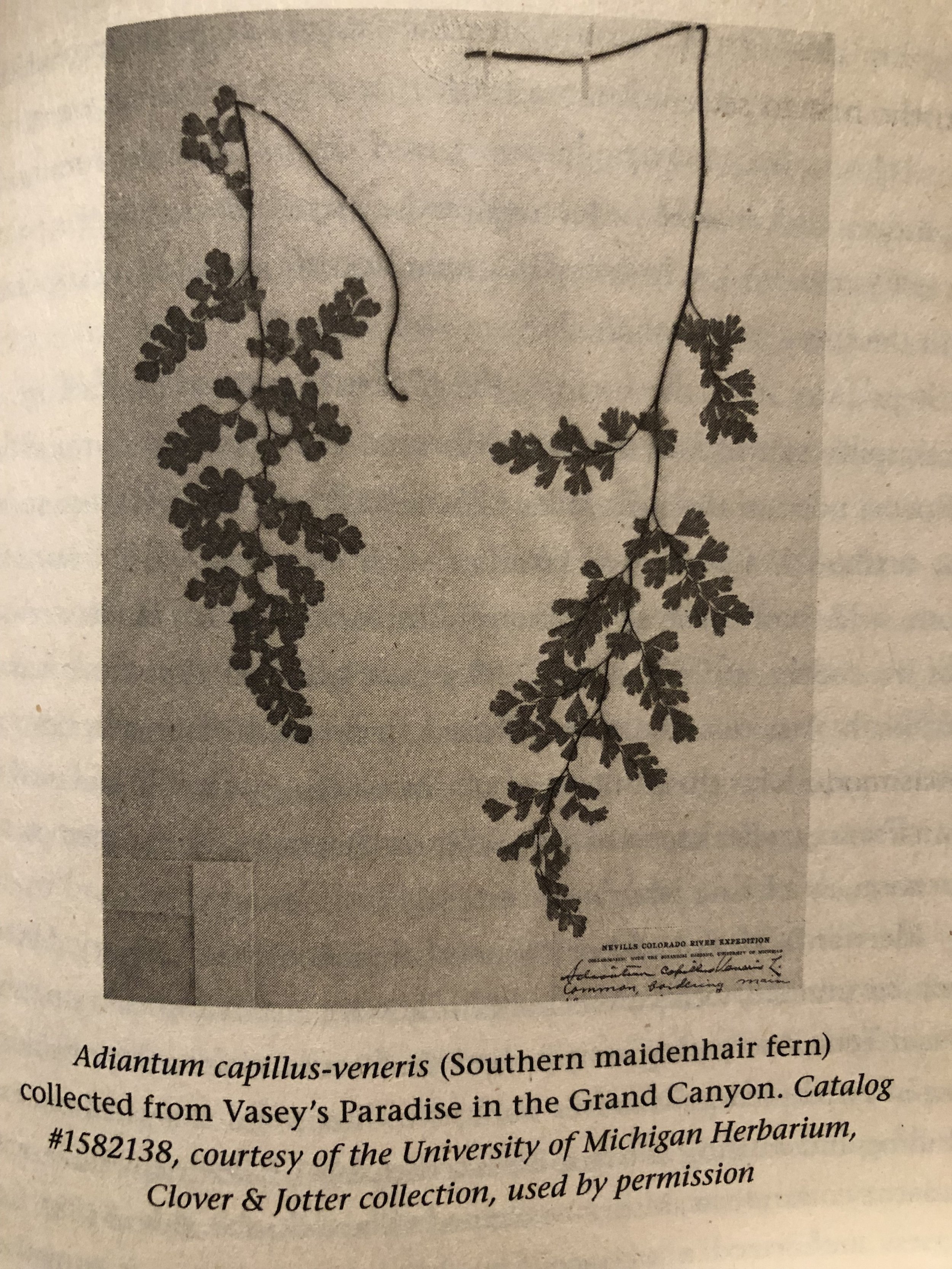

At a time when it was commonly felt that the Colorado River was a “mighty poor place for women,” Clover and Jotter often worked harder than the men. One morning after running the rapids, the expedition’s four boatmen docked on a sandbar at river mile 30—a natural garden named Vasey’s Paradise. While stopped there, the two women identified and collected scarlet monkey flower, Western redbud, Southern maidenhair fern, horsetail, watercress, side-fruited crisp moss, Stansbury cliffrose, and Longleaf brickellbush.

Sevigny describes the events that cloudy late-July morning. “Clover and Jotter jumped out of a wooden boat and collected furiously while the men showered under a waterfall and then waited for the women to make and serve them lunch.” “We have spoiled them completely,” Clover noted in her journal. In a later entry, she described the two women collecting plants while racing through the canyon. “It was just part of the day’s work to make a flying leap for shore, to climb steep cliffs after plants, and to get photographs.”

In “Brave the Wild River,” Sevigny points out that it was not easy back then for the two female botanists. At a time when it was thought that such a risky venture in pursuit of science should only be taken by men, the idea that women should or could do such things was unimaginable and even scandalous. Even at the end of their journey, Clover and Jotter were described by journalists as “schoolma’ams” with “copper-tanned cheeks.” One photographer insisted on posing Lois Jotter holding a powder puff and hand mirror, something they had grown used to from journalists covering their adventure. They would have preferred to be recognized as women of science.

As part of Women’s History Month this year, the NPS celebrated the two pioneering botanists who made history studying and learning within the canyon walls. By the end of the trip, Clover and Jotter had identified five different plant zones and over fifty plant species. They’d also found four previously unidentified species. “With their tenacity, they blazed a trail for other women to follow their footsteps. From the Colorado River to the rim of the canyon, women in science have had a major impact on how we understand this park.”

Author Melissa L. Sevigny, who rafted the Grand Canyon with a botany crew herself in the fall of 2021, concludes, “Their story matters…. Like others before them, Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter valued their curiosity about the world more than their presumed place in it. They go ahead and, like stars reflected on the river, show the way.”